|

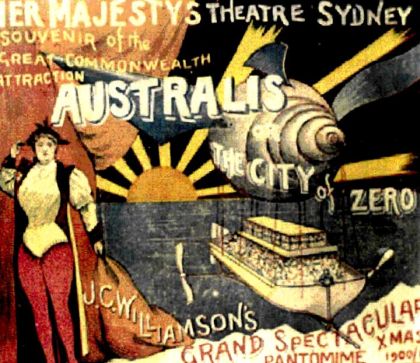

| JC Williamson's

Federation Pantomime Australis or the City of Zero |

Predicting the future is

what we do to prepare ourselves for tomorrow.

Some predictions prove to be fanciful while others turn

out to be uncannily accurate. JC Williamson, in his

Federation pantomime Australis anticipated that in the

year 2000 New Zealand would be our seventh state and the

Antarctic would be the capital of Australia. The French

artist Villemard imagined in 1910 that one hundred years

later we would be able to send mail by dictating into a

loudspeaker and we would be listening to

audio-newspapers. Some would argue that George Orwell

foresaw with unsettling accuracy in his novel 1984 a

world run by Big Brother through – at least in Australia

- the Ministry of Truth.

Libraries have so far survived the first phase of the

information revolution. But what is in store for the

coming decades?

CHECKING THE REARVIEW MIRROR

When gearing up for the

future, it is instructive to look at the past. Richard

Neustadt and Ernest May promoted the necessity of doing

so as a way of avoiding future mistakes. [1]

My readily available pieces of history are the articles

I’ve written on conferences and trends for Online

Currents during the past decade. What sort of story do

they tell?

As the new millennium drew near, the library world was

mired in uncertainty. At the Australian Library and

Information Association (ALIA) Information Online

Conference 1999, rapporteur Neil McLean summed it up.

The internet was the greatest cottage industry in the

world but more discussion was needed on how to make the

most of it. He urged delegates to take comfort in

uncertainty, find a new centre of gravity, think long

term, re-think paradigms, form new alliances, re-think

architectures, examine intermediary roles, and match

people with new opportunities and resources. Provocateur

Tony Barry reckoned libraries would be by-passed or take

on a more advisory role, major search engines would go

down the gurgler, and there would be a rise in

specialised online indexes. Peter Lyman, from the

University of California, Berkeley, warned about getting

too carried away with technology. It does not produce

productivity gains, he said, but it does drive changes

in the way work is organised.[2]

At the Ozeculture conference in 2001, John Rimmer from

the National Office of the Information Economy (NOIE)

offered a map and a compass to find directions in a new

economy based on the creation and exchange of

information. For the cultural sector, he said, growth

would be dependent on successful navigation of

apparently contradictory and competing forces, making

the most of converging technologies and the

restructuring of industries. There was talk of

allocating investment funds in a more sustainable

fashion.[3]

A couple of months later, the Computing Arts Conference

at the University of Sydney depicted the work of

academia in the digital realm. In a year which also

witnessed the attack on the twin towers in New York and

the birth of Wikipedia, Edward Zalta gave the stand-out

presentation on how the Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy was able to marshal the forces of scholars to

produce a free online product. Government, academic,

cultural heritage and business sectors, however, seemed

to be running on separate exploratory tracks.[4]

The ALIA Biennial Conference in 2002 set out to help

librarians position themselves in an Australian

knowledge industry then valued at $171 billion.

IBISWorld’s Phil Rhuven drew attention to the extent to

which librarians were merely bit players in the

information game. Peter Crawley, headmaster of Knox

Grammar School, anticipated a future fascination with

Facebook and Twitter by saying that gossip helped us

process information. Various speakers touched on the

importance of infrastructure, connectivity, content,

competencies, research and innovation. One of the aims

of the conference was to promote discussion on a

national plan, but there was some confusion as to

whether it was to be a plan for ALIA or for the sector

at large. Some doubted that national information plans

really work. Crawley cautioned against anecdotal

thinking: “if you cut and paste your future, you will

cut and paste you’re irrelevancy.” McLean asserted there

would be no quick way to work through the future: “we

may need to live through a generation of

uncertainty.”[5]

The Ozeculture conference in 2002 was devoted to the

challenges of marrying cultural heritage with

information technology. Government adviser Terry Cutler

set the mood by saying we were still in the primitive

stage of the technology revolution. “There is not enough

disorder, one of the ingredients of invention.” The

challenges included long-term thinking, linking

pre-internet and past-internet collections and “moving

into the spaces between the main tracks”. NOIE’s David

Kennedy, sketching out findings of the Creative

Industries Cluster Study Report, called for more

industry data to guide decisions and the creation of

clusters in which small players would feed off big

players. There was talk about the need for

“whole-of-government” approaches.[6]

In 2003 it appeared libraries and kindred spirits were

more positive about their role in the information

revolution. At the ALIA Information Online Conference

that year, the need for clarity emerged as a common

theme in a number of papers devoted to roles, strategies

and services. Generalisations tended to muddy positions.

Roger Summitt, in the final session, urged delegates to

‘distinguish between different types of information

needs, from broad public needs to the needs of the

commercial workplace.’[7]

In 2003, the Australian Senate conducted its inquiry

into the role of libraries in the online environment.

The committee had formed the reassuring impression that

Australia was remarkably well served by its library

services. The “propensity [of libraries] to band

together and to share resources is an object lesson in

what can be achieved by cooperation across

jurisdictional boundaries.” It was, however, concerned

that many outstanding services appeared not to be widely

known and that libraries appeared to be taken for

granted rather than valued. It recommended in principle

the notion of a national information policy and

anticipated the Cultural Ministers’ Council would review

the need for such a policy. Other recommendations

touched on national leadership, connectivity, content,

legal deposit, skills, promotion and funding.[8]

Two other articles in 2003 (Arts Hub Australia and

Who’s

Who in Australia Live!) looked at responses by local

commercial publishers to the emerging online

environment.[9] And, in the same year, the Australian

Bureau of Statistics published a web-based compendium of

metrics for Australia’s knowledge-based economy and

society, involving a suite of indicators representing

contexts, innovation and entrepreneurship, human

capital, information and communications technology, and

economic and social impacts.

At the 2005 ALIA Information Online Conference, Colin

Webb, felt the time had arrived to change the metaphor

to describe how librarians were coping in the online

revolution. In1995, he said, we had talked of the

internet in terms of “drinking from a fire hose,” but in

2005 it felt that we were now preoccupied with putting

out bush fires. As major overseas reports presented a

picture of sector fragmentation, duplicated effort and

resources, lack of leadership and lack of influence in

the higher reaches of political power, there was an

expectation that some coherence would be forged locally

by the newly-established Collections Council of

Australia.[10]

In the same year, it was time to explore the purpose and

dynamics of library and information associations. The

internet had made it easier for librarians to find

professional information, but it had also made it more

difficult for some associations to retain members.

Business acumen, it seemed, was needed to harness a

diverse marketplace in which values and volunteerism

continued to play an important part.[11]

The ALIA Information Online Conference in 2007 explored

the changing nature of library services as we moved

closer to a Semantic Web. Joanne Lustig’s analysis that

compelling disruptive forces were triggering a period of

exponential change was balanced by more circumspect

commentary that questioned the need for exponential

change. Walt Crawford, for example, was sceptical about

the need for a revolution, but he thought Library 2.0

developments would make libraries more interesting, more

relevant and better supported.[12]

The high dependency of libraries and other cultural

institutions on government funding prompted a closer

look at government policies in 2009. Creative Nation

in

1994 had been followed by a steady trickle of Government

reports and policies about the information economy and

the cultural heritage and creative industry sectors.

Future prospects appeared to rest with the Collections

Council of Australia, which had been created by the

Howard Government in 2004. The Council’s Australian

Framework for Digital Heritage Collections presented

priorities for further collaboration under nine broad

needs. It called for additional government funds and a

more sensible way of allocating funds, only to find its

own funding had been withdrawn by the Labor

Government.[13]

The ALIA Information Online Conference in 2009 explored

the buzz around the need for transformative change,

spending money wisely, and working creatively with

others. Two main threads were that the changing

behaviours of users would drive this change and

librarians should jettison their risk-averse bent in

favour of being more innovative.[14]

The Museums Australia national conference in 2009 drew

out reflections on how museums were connecting with

information seekers. In considering the museum sector’s

tortured attempts to deal with standards and aggregation

since the 1920s, a report by Mary Elings and Günter

Waibel was called into play as a reminder that

successfully connecting library, archive and museum

collections hinges on the emergence of a more homogenous

practice in describing like materials in different

institutions. While it is easy to map data structures,

data content variance prohibited economic plug-and-play

aggregation of collections.[15]

The article Mastering Digital Lives in 2010 reviewed

personal digital practices in a Web 2.0 world and the

work of cultural heritage institutions to address

attendant challenges through projects such as PARADIGM,

the Digital Lives Project, and OCLC’s Sharing and

Aggregating Social Metadata study. In an age when

everyone with a computer has become an archivist, for

cultural heritage institutions risk management had

gained new prominence as the name of an old game.[16]

The VALA conference in 2010 drew out thoughts about the

Semantic Web, cloud computing and linked open data. The

information revolution was described is an evolution

with innovative outbursts. An organic Web was leading us

to a linked up future in which language was the

impediment as well as its currency. For the Semantic Web

to work, Tom Tague urged, we need to clean up the dirty

data in the World Wide Web. Dealing with dirty data

would involve discipline in the back end at a time when

the back end was an open office. Librarians were urged

to step up their role in the revolution. Stepping up

would involve strengthening cooperation, developing

systems and applying standards.[17]

The ALIA Information Online Conference 2011 got underway

as the tipping point for e-books was about to arrive.

Borders and Angus and Robertson were about to be placed

into voluntary administration. Jim McKerlie urged

librarians to find new paradigms to help libraries do

more with less. Darwinism, he said, would prevail: there

would be winners and losers. Other commentators pointed

to the capacity of social media to change the nature of

information production. Those in the parallel streams of

the conference seemed to have their finger on the pulse:

persistent change was part of doing normal business.[18]

The ALIA Biennial conference 2012 coincided with the

rush to mobile devices and the need for designing better

library interfaces. Michael Kirby urged us not to forget

values in giving service. As technology continued to

drive all before it, there were grounds for librarians

to look forward to the future with optimism.[19]

Jane Douglas reported on the 2013 ALIA Information

Online Conference in Brisbane. The attendance figures

for Australia’s biggest library conference had dropped

dramatically. Its theme was “be different, do

different”. Speakers sought to position librarians as

knowledgeable intermediaries in a world of overwhelmed

users. Minds were again focussed on prompting the value

and indispensability of libraries. There were calls for

changes to buildings, systems, and services based on an

understanding of the marketplace.[20]

Articles on the changing nature of library and archival

services in the fields of the arts and health sectors

revealed challenges in specialised areas exposed to new

online opportunities, complex IT requirements, and

half-baked management solutions.[21]

VIEWS ABOUT THE ROAD AHEAD

In 2014, the economic and

social forces still appear to be daunting.

The CSIRO, stepping into the shoes of futurists John

Naisbett and Patricia Aburdene, has identified 6

megatrends that may affect the way we operate. Three of

them may influence the future of libraries. We will have

to do more with less because the earth has limited

resources. Individuals, communities, governments and

businesses will be immersed into the virtual world to a

much greater extent than ever before. There will be

rising demand for experiences and social relationships

over products.[22]

The predictions are amplified by other crystal ball

gazers. The World Economic Forum sees intensifying cyber

threats, inaction on climate change, a diminishing

confidence in economic policies, a lack of values in

leadership, an expanding middle class in Asia, and the

rapid spread of misinformation online.[23] Among the

predictions of the Futurist Magazine are things that are

already happening. Big data will help anticipate our

every move. Buying and owning things will go out of

style. Quantum computing could lead the way to true

artificial intelligence. Atomically precise

manufacturing will make machinery, infrastructure and

other systems more productive and less expensive. It

also predicted populations would shrink by 2020 and our

wealth will shrink with them.[24]

The current state of the internet flags geopolitical and

social shifts. There are now more than 2.2 billion email

users, who transmit 144 billion pieces of email per day.

Around 70% of all email traffic is spam. There are more

than 634 million websites. About half of the 2.4 billion

internet users worldwide are from Asia. Facebook has

more than 1 million active users, Twitter more than 200

million who send 175 million tweets every day. There

were 1.2 trillion searches on Google in 2012. More than

1.1 billion people have smartphones. We watch 4 billion

hours of video a month on YouTube.[25]

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering

proffers likely technological directions. Mobile and

cloud computing are converging to create a new platform

of unlimited, more seamless computing resources. New 3D

printing tools and techniques are empowering everyone to

create new devices more quickly, cheaply and easily.

Exploding interest in Massive Open Online Courses is

generating a need for technology to support new learning

systems and styles. There will be a continuing battle to

balance individual privacy and the interests of the

system at large. Big data is generating datasets that

are increasing exponentially in both complexity and

volume, making their sharing and archiving among the

great challenges of the 21st century.[26]

The International Federation of Library Associations has

pinpointed nuances in the transformative impact of new

technologies. In its Trend Report, it says

technologies will both expand and limit who has access

to information. Online education will democratise and

disrupt global learning. The boundaries of privacy and

data protection will be redefined. Hyper-connected

societies will listen to and empower new voices and

groups.[28] An earlier report by the American Library

Association’s Office for Information Technology Policy

makes similar observations and concludes that the future

is mainly about collaboration.[28]

The signs of change can be found in a number of reports

about libraries in the United States, the United Kingdom

and Australia.

The Pew Research Centre’s report, Library Services in

the Digital Age, establishes the importance of public

libraries in the minds of Americans. Public libraries

are trying to adjust their services to new realities

while at the same time serving patrons who rely on more

traditional resources. The availability of free

computers and internet access now rivals book lending

and reference expertise as a vital service. Americans

would embrace even wider uses of technology at libraries

such as online research services, apps-based access to

materials and programs, the ability to check out books,

movies or music without having to go to the library, and

classes on the use of technology.[29]

The slogan on a media release from the Institute of

Museum and Library Services report on American public

libraries sums up the challenges they face: “Libraries

doing more with less, local government taking larger

funding role”. Although physical visits increased and

circulation figures were the highest in ten years,

expenditures decreased for the first time since 2001 and

local governments have taken on a greater support role.

The recession has had an impact on the public library

workforce, which has decreased by 3.8% since 2008.

Librarians made up one-third of all library staff.[30]

The Association of Research Libraries gives a picture of

what has been happening in research libraries. Over the

past 20 years, there has been an overall drop of 10% in

staff numbers, a 29% decline in total circulation, and a

staggering decline of 65% in reference transactions.

Inter library loan traffic increased by 158% in the same

period, but has started to drop. In the period 1986-2011

spending on serials soared 402%. [31]

In the United Kingdom, government austerity measures

appear to be having an even greater impact on libraries.

According to a survey by the Chartered Institute of

Public Finance and Accounting more than 200 public

libraries were cut in the UK in the period 2011/12.

Staff numbers dropped by 8%, while the number of

volunteers working in libraries increased by 9% (on top

of a 23% hike in 2010/11). The number of books issued by

libraries also decreased, as did the number of active

borrowers.[32] With overall cuts of 40% in the costs of

running government departments between 2010 and 2016,

library bodies are anticipating further grim news.[33]

The release of Arts Council England’s report Envisioning

the Library of the Future has generated fresh cries for

help. John Dolan, Chair of the Chartered Institute of

Library and Information Professionals, said “without

stronger political leadership supporting a clear

national vision it’s going to be a struggle to deliver

consistently high-quality and relevant library services

in communities across the country.[34] Alan Davey, Chief

Executive of Arts Council England, pinpointed

collaboration is key element in placing the library as

the hub of the community, making the most of digital

technology, and delivering the right skills for those

who work in libraries.[35]

Australia’s public libraries, according to a report by

SGS Economics, deliver benefits that are worth nearly

three times the cost of running them. With a net annual

benefit of $1.97 billion, it makes a case for increased

levels of funding for public library services.[36] ALIA

is reviewing options for its future direction and has

released a paper to promote discussion on the future of

all types of libraries around three themes: convergence,

connection and the golden age of information.[37] The

Victorian Government is reviewing future options,

including the level of funding and funding

accountability provided by the three tiers of government

to support public library services.[38]

Two American colleagues draw some of the threads

together.

OCLC’s Lorcan Dempsey says we are at a “re-set moment”

in which collaboration has to move from the margins to

the core.

At the LIANZA Conference 2013 and in a related article,

he said reduced transaction costs in a network

environment are reshaping whole industries and libraries

will be no exception. We are experiencing an accelerated

transition from print to digital materials, from bought

material to licensed products. Shared and third party

arrangements are being used to manage related processes.

There is trend from institutional systems to shared

systems. Library spaces are being redefined to encourage

interaction between people and specialist services.

Libraries must build their services around user

workflows. Distinctive services are emerging in which

library expertise is being promoted as a key element of

library value. An enterprising mentality is required to

implement changes.[39]

Clifford Lynch, the director of the Coalition of

Networked Information, in The Public Library in 2020,

anticipates a profound transition for public libraries.

Some things won’t change much, but the accessibility of

electronic information from other services is forcing

public libraries out of their traditional marketplace.

As the economic circumstances move from a world in which

information resources are sold to one in which they are

licensed, there will be a flash-point as electronic

materials begin to dominate. The good news is that

public libraries will be able to reposition themselves

as cultural memory services by forging closer alliances

and partnerships with historical societies, local

government records services, businesses and

universities. There may be a move to membership-based

funding strategies as a means of financial survival. We

may see library mergers or close alliances of

geographically remote libraries. They may become

creators of specialised content and publishers of

independent authors to complement the commercial

mainstream.[40]

Lynch and David Fenske, in a conversation at Drexel

University's College of Computing & Informatics in

October 2013, reflected on the future of libraries and

informatics in the scholarly environment. Among the

issues to be managed are big data and data curation, the

tensions between private rights and public good, cyber

security and misinformation, and personal digital

archives. There is a need to develop services in a way

that is “equal to the pace of public expectations.” [41]

PULLING OURSELVES TO WHERE WE WANT

TO BE

Will the future of libraries involve more of the same or

something completely different?

Some would say it is a question not worth answering

because the planet may not survive very much longer. Ugo

Bardi references the wisdom of Seneca in an article

about the possible end of civilisation caused by

inaction on climate change: “It would be some

consolation for the feebleness of ourselves and our

works if all things should perish as slowly as they come

into being; but as it is, increases are of sluggish

growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.” The Roman

civilisation took seven centuries to peak and about

three centuries to fall. But, as a way of lacing a

daunting challenge with a dose of optimism, Bardi does

take solace in the words of Robert Louis Stevenson:

“Everybody, sooner or later, sits down to a banquet of

consequences.”[42]

The future may be less dramatic than some futurists

predict. Joss Tantram says it will most probably lie

somewhere “between the worst doom-mongering predictions

and the most optimistic techno-utopian dreams.” But it

will be shaped by our passivity or the action we take.

It is not magic we require for a sustainable future,

just co-ordinated will and intent.[43]

The information revolution continues to evolve with

occasional surprises. Bill Davidow has warned of a

future catastrophe: the internet may be the conduit for

the next global crisis. Social media offer the illusion

of greater democracy, the promise of productivity, and

smaller thoughts. Some say the information revolution

has stalled, while others say it takes a while for

revolutions to play out.

The things we can control may be more important than the

things we can’t control. Frank Spencer and Yvette

Montero Salvatico, for example, in arguing that

predicting the future is a waste of time, have said we

should pull ourselves toward to where we want to be.

Guiding narratives driven by values, aspirations and

good design are a more effective compass in navigating

our complex and volatile landscape.[44]

How do we pull ourselves to

where we want to be?

The uncertainty felt by

librarians in 1999 has not abated and is now an accepted

norm. The Guardian reminds us that ideas contrary to a

prevailing dogma are likely to be attacked when they

first appear. Innate conservatism will destroy

half-baked ideas but hostile criticism will be honed by

persistent minds. Uncertainty, accompanied by confusion

and discovery in equal measure, “will always remain a

labyrinth.”[45]

The call for leadership has

been constant in conference deliberations, but what does

leadership involve and who’s to be the leader? In the

2002 ALIA Biennial conference, Neil McLean detected “a

yearning for leadership”, but he also put the finger on

the dysfunction of library tribes. When creating a new

infrastructure, he cautioned against making

generalisations and searching for a one-size-fits-all

solution. Creating a new infrastructure, Paul Raven

reminds us, is a staggeringly complex and messy job. We

are often tempted to make it someone else’s problem.[46]

Plans are one of the

necessities although some well-positioned commentators

have expressed cynicism about grand visions and the

likelihood of broad consensus. Planning is a process as

well as a recipe, particularly in world where the things

driving the action are constantly changing. Instinct

sometimes has to override well honed plans.

The call for solutions has

often been accompanied by the call for innovation when

the need may actually be the need for more common sense.

Some have argued that innovation is an overrated concept

and an overworked word. Librarians are usually part of

someone else’s business. With limited control over their

finances, they are not well placed to take risks. But

they are adept at making the most of someone else’s

innovation.

Revolutionary collaboration is widely proclaimed as an

overriding necessity, but deep collaboration in the

cultural heritage sector has been difficult to muster.

The experience of the National Digitisation Information

Infrastructure Preservation Program in the United States

highlighted the difficulty of collaboration in diverse

environments. Managing institutional interests is not

easily transferable to sector-wide, multi-jurisdictional

programs. Even within the same domain, there are

barriers to collaboration. Although partners share a

common interest, their work in diverse communities is

not necessarily conducive to thinking and working as a

larger network. Interoperability challenges become

greater as user communities broaden their interest.

Solutions are not necessarily found by looking for

silver bullets.[47]

Leah Prescott and Ricky Erway have underscored the

institutional, technical and metadata challenges. The

apparent differences in approaches by libraries,

archives and museums might be insurmountable, they wrote

in Single Search, if not for the fact that they share

one value in common: their desire to simplify resource

discovery and delivery.[48]

Government assistance is necessary at a time when there

will be increasing pressure on the public purse.

Marshalling the interest of cultural heritage

institutions calls for compelling incentives, but the

government record has not been encouraging on this

front.

In Australia, the Howard government created the

Collections Council of Australia, but the Labor

government closed it down - along with the wrongly-named

Collections Australia Network - with no explanation. The

Labor government’s attempt to make high speed broadband

as easy as turning on water has been replaced by

Coalition plans based on the idea of reinventing the

local telephone box. In the United Kingdom, the Cameron

Government disbanded the Museums Libraries and Archives

Council. The Institute of Museum and Library Services

has survived the recession in the United States.

Future government decisions will be shaped by cultural

heritage sector recommendations on how to spend taxpayer

funds. Without a respected coordinating body to make

sense of the complexities and high order priorities,

actions will be left largely in the hands of those with

control over major institutional spending.

The route to the future is probably the same as it was

when Neil McLean sketched it out in 1999: take comfort

in uncertainty, find a new centre of gravity, think long

term, re-think paradigms, form new alliances, rethink

architectures, examine intermediary roles, and match

people with new opportunities and resources.

But at least we now have Trove as an established path to

some of the hidden treasures and as a platform full of

promise for future collaborative endeavours.[49]

End notes

[1] Neustadt, E and May E. Thinking in time: The uses of

history for decision makers. (The Free Press, 1988).

[2] Bentley P, “Shifts in

the sand: Information Online 2001” (2000) OLC v14 n10: 2

[3] Bentley P, “Australian culture seeks e-business

direction: Impressions of the Ozeculture Conference,

Melbourne, June 2001” (2001) OLC v16, n7: 16

[4] Bentley P. “Digital

resources for research in the humanities: The computing

arts conference, Sydney, September 2001” (2001) OLC v16,

n10: 13

[5] Bentley P, “Searching

for the next sigmoid curve: The ALIA Conference 2002”

(2002) OLC v17, n6:19

[6] Bentley P, “Driving

Australian e-culture: The Ozeculture Conference 2002”

(2002) OLC v17, n8: 10

[7] Bentley P, “Information

Roles: A Question of Maturity? A view of the Information

Online Conference 2003, Part 1” (2003) OLC v18, n1: 7;

Bentley P, “Stinking libraries, disappearing librarians

and the invisible Web: A view of the Information Online

Conference 2003, part 2” (2003) OLC v18, n3: 23

[8] Bentley P, “Libraries in

the online environment, part 1: Contexts” (2004) OLC

v19, n1: 11; Bentley P. “Libraries in the online

environment, part 2: Challenges” (2004) OLC v19, n4:15;

Bentley P, “Leading libraries, archives and museums in

an online environment: A Senate Inquiry postscript”

(2004) OLC v19, n6:14

[9] Bentley P, “Arts Hub

Australia” (2003) OLC v18, n8: 12; Bentley P, “Who’s Who

in Australia Live!” (2003) OLC v18, n10:10

[10] Bentley P, “Fighting

bush fires: The 2005 Information Online Conference”

(2005) OLC v20, n2: 6

[11] Bentley P, “Baking a

new pie: Library & information associations in an online

world” (2005) OLC v20, n9: 3

[12] Bentley P, “Embedding

librarians in a world of dirty data: The Information

Online Conference 2007” (2007) 21 OLC 231

[13] Bentley P, “The digital

economy dance: Getting into step with government policy”

(2009) 23 OLC 13

[14] Bentley P, “Getting in

the game of creative collaboration: The ALIA Information

Online Conference 2009” (2009) 23 OLC 1

[15] Bentley P, “Changing

the horseshoe on a galloping horse: Connecting museums

to information seekers (2009) 23 OLC 186

[16] Bentley P, “Mastering

digital lives: Cultural heritage institutions tackle the

Tower of Babel” (2010) 24 OLC 67.

[17] Bentley P, “Talking up

the back end of an evolving revolution: The VALA

Conference 2010” (2010) 24 OLC 121

[18] Bentley P, “Winning and

losing in a world of new paradigms: the ALIA Information

Online Conference 2011 - part one” ((2011) 25 OLC 111;

Bentley P, “Operating in a world of ornate variations

and tipping points: The ALIA Information Online

Conference 2011 – part two” (2011) 25 OLC 1

[19] Bentley P, “Reinventing

libraries for the mobile flaneurs: The odyssey

continues” (2012) 26 OLC 295

[20] Douglas J, “ALIA

Information Online 2013” (2013) 27 OLC 195

[21] Bentley P, “Evolving

stages: Australian performing arts online” (2005) OLC

v20, n6: 14; Bentley P, “Being there without being

there: the Arts in the Age of YouTube” (2012) 26 OLC

171; Bentley P, “Catching lighting in a bucket:

Archiving the performing arts in the digital age” (2012)

26 OLC 171; Bentley P, “Body knowledge in bytes; the

health industry gears up for the 21st century” (2013) 27

OLC 186

[22] Naisbett, J and

Aburdene P Megatrends 2000 London: Pan, 1990; CSIRO,

Our

Future World, 23 April 2010, updated 2 October 2012

http://www.csiro.au/Portals/Partner/Futures/Our-Future-World.aspx.

23 April 2010,

[23] Columbus L, “Top Ten

Trends Of 2014 From World Economic Forum Underscore The

Need For Cloud Security” Forbes 15 November 2013

http://www.forbes.com/sites/louiscolumbus/2013/11/15/top-ten-trends-of-2014-from-world-economic-forum-underscore-the-need-for-cloud-security/?utm_destname=techl0g&utm_desttype=twitter

[24]Tucker P, “Top Ten

Forecasts for 2014 and Beyond” The Futurist 6 October

2013

http://www.wfs.org/blogs/patrick-tucker/futurist-magazines-top-ten-forecasts-for-2014-and-beyond

[25] “Internet 2012 in

numbers” Pingdom 16 January 2013

http://royal.pingdom.com/2013/01/16/internet-2012-in-numbers/

[26] “Top 10 Tech Trends in

2014” IEEE Computer Society

http://www.computer.org/portal/web/membership/Top-10-Tech-Trends-in-2014

[27] International

Federation of Library Associations, Trend Report,

(2013)

http://trends.ifla.org/

[28] Hendrix JC, Checking

Out the Future: Perspectives from the library community

on information technology and 21st-century libraries,

ALA Office of Information Technology Policy, Policy

Brief no 2, February 2010

http://www.ala.org/ala/aboutala/offices/oitp/publications/policybriefs/ala_checking_out_the.pdf).

[29] Zickuhr K, Rainie, L

and Purcell L, Library Services in the Digital Age, Pew

Research Centre 23 January 2013

http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2013/01/22/library-services/

[30] Institute of Museum and

Library Services, “2010 public library survey results

announced” 22 January 2013

http://www.imls.gov/imls_2010_public_library_survey_results_announced.aspx

[31] Kyrillidou M,” Research

library trends: A historical picture of services,

resources, and spending” in (2012) Research Library

Issues: A Quarterly Report from ARL, CNI, and SPARC

(280): 20-27. (http://publications.arl.org/rli280/20).

[32] Russell V, “Library

closures hit 200 last year” The Chartered Institute of

Public Finances and Accountancy 10 December 2012

http://www.publicfinance.co.uk/news/2012/12/library-closures-hit-200-last-year-cipfa-survey-shows/

[33] Chartered Institute of

Library and Information Professionals, “What the

Government’s spending review means for library and

information services”

http://www.cilip.org.uk/cilip/news/what-government-s-spending-review-means-library-and-information-services

[34] Chartered Institute of

Library and Information Professionals, “Call for

political leadership on libraries” 23 May 2013 http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20130626073405/http://www.cilip.org.uk/news-media/pages/news130523.aspx

[35] Arts Council England,

A

response to the Envisioning the library of the future

report, by Arts Council England Chief Executive Alan

Davey, May 2013

http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/media/uploads/pdf/The_library_of_the_future_May_2013.pdf

[36] Australian Library and

Information Association, “Libraries: a better investment

than gold” 14 May 2013

http://www.alia.org.au/media-releases/libraries-better-investment-gold

[37] Australian Library and

Information Association, Library and information

services: The future of the profession themes and

scenarios 2025 and related material

http://aliafutures.wikispaces.com/

[38] Premier of Victoria,

“Tomorrow’s Library report tells a compelling story” 3

December 2013

http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/5560-tomorrows-library-report-tells-a-compelling-story.html

[39] Dempsey L, “Keynote

presentation at LIANZA conference 2013”5 November 2013

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nAev2DUJe1U; Dempsey L,

"Libraries and the informational future: aome notes"

(2012) 32 Information Services & Use: 203–214

http://iospress.metapress.com/content/q74467n473057274/fulltext.pdf

[40] Lynch, C The public

library in 2020

http://www.cni.org/publications/cliffs-pubs/public-library-2020/

[41] Lynch C and Fenske D, A

Conversation [at] Drexel University College of Computing

& Informatics 4 October 2013

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BjPxIkKHHLA

[42] Bardi U, “The Seneca

effect: Why decline is faster than growth” Business

Insider Australia, 31 August 2011

http://www.businessinsider.com/the-seneca-effect-why-decline-is-faster-than-growth-2011-8

[43] Tantram J, “Preparing

for a sustainable future requires co-ordinated will, not

magic” The Guardian 23 July 2013

http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/preparing-sustainable-future-will-magic

[44] Spencer F and Salvatico,

YM, “Why predicting trends doesn't help prepare for the

future” Fast Company 20 November 2013

http://www.fastcoexist.com/3021148/futurist-forum/why-predicting-trends-doesnt-help-prepare-for-the-future

[45] “In praise of

uncertainty” The Guardian 9 December 2013

http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2013/dec/09/in-praise-of-uncertainty-genes

[46] Raven, PG, “The artist

as engineer: we need to talk about infrastructure” The

Guardian 4 September 2013

http://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/culture-professionals-blog/2013/sep/04/artist-engineer-infrastructure-means-matters

[47] Bentley P, “The digital

economy dance: Getting into step with government policy”

(2009) 23 OLC: 13

[48] Prescott L and Erway R,

Single Search: The Quest for the Holy Grail, OCLC

Research July 2011

http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2011/2011-17.pdf?urlm=162962

[49] Trove: trove.nla.gov.au/

Non-commercial viewing,

copying, printing and/or distribution or reproduction of

this article or any copy or material portion of the

article is permitted on condition that any copy of

material portion thereof must contain copyright notice

referring "Copyright ©2013 Lawbook Co t/a Thomson Legal

& Regulatory Limited." Any commercial use of the article

or any copy or material portion of the article is

strictly prohibited. For commercial use, permission can

be obtained from Lawbook Co, Thomson Legal & Regulatory

Limited, PO Box 3502, Rozelle NSW 2039,

www.thomson.com.au